"The space in which we live, which draws us out of ourselves, in which the erosion of our lives, our time, and our history occurs, the space that claws and gnaws at us, is also, in itself, a heterogeneous space. In other words, we do not live in a kind of void, inside of which we could place individuals and things. We do not live inside a void that could be colored with diverse shades of light, we live inside a set of relations that delineates sites which are irreducible to one another and absolutely not superimposable on one another."

-- Michel Foucault, Heterotopia, of Other Spaces

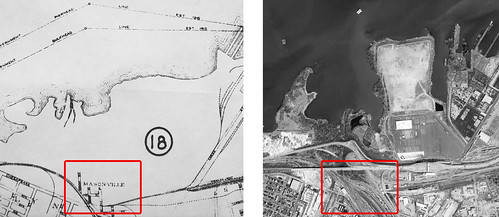

(Masonville Cove in c. 1925, labeled 'Changeable Area'. On the left is Reed Bird Island.)

Masonville Cove is a large, mostly open, waterfront plot in South Baltimore. This area is currently the site of a complex engineering project overseen by the Maryland Port Administration: the Masonville Cove Dredged Material Containment Facility. Geographically, the site breaks down into three main pieces. From west to east, call them the Claw, the Head, and the Shipyard.

(Masonville Cove in 1954 [left], and 2005 [right])

The Claw is conspicuous, jumping out of the gmaps aerial photo like a mutant appendage. Between the double pressures of development and industry, this much feral openspace on the waterfront is an anomaly, even for the spottily derelict Middle Branch. It is heavily vegetated, but walking the site, feeling the mossy bricks, ceramic powerline insulators and huge concrete blocks underfoot, one sees that this is really just a big pile, a ground made of stuff. The plants, in some cases huge trees and dense woods, are only the most recent (now the second most recent) system to infiltrate, overlay, and, however incompletely, organize this space.

(Masonville Cove coastline, 1819-2008)

The record in this area is lossy and unreliable, but old maps seem to show no Claw before the early 20th century. Instead of a peninsula, there's a bay, the original Cove. The shallows in the Cove are the product of churn from the mouth of the Patapsco River adjacent, carrying runoff from development in old mill towns and new subdivisions upstream.

In 1904, there was a catastrophic fire in Baltimore. Firefighters from Philly and DC were unable to connect their hoses to Baltimore's hydrants. The fire predated the advent of standardized infrastructure, even between cities that were relatively close. The oldest blocks in the center of downtown were destroyed, but there was no loss of life. The gutted, emptied core allowed new city systems to be upgraded with extra capacity, as modernized water, sewer, and storm drains were laid beneath newly widened streets.

(The Baltimore Fire of 1904)

The fire took down over 1500 buildings, the debris had to go somewhere. In maps made after 1904 there is a new peninsula at Masonville Cove: the stub of the Claw. Locals pass down the story of wreckage hauled south to Masonville in barges. Note the cast iron columns at the lower left of the photo above, compare them to a pile of cast iron columns onsite below. Foundries in the city, retooled after the Civil War, had produced over 100 buildings in Baltimore with cast iron fronts, and almost as many more of these modular precast facade sytems were exported via rail to other cities. From New Orleans in the south to SoHo in the north, much of the iconic cast iron architecture on the east coast was made in Baltimore. The 1904 fire destroyed about 25 cast iron front buildings.

(Cast iron columns found onsite at the Claw)

Beside the layers of rubble, there are other, newer and more toxic layers of ash and sand, possibly mixed with arsenic and lye. In the middle of the 20th century this site, originally composed of destruction and debris, was used as a yard for the preparation of new construction material: concrete and pressure treated lumber. In the older portions of the peninsula, future cleanup is complicated by the many large trees growing between and among the chunks of masonry. Families of wild deer live and forage here. In the newer fields further out, large plants will not grow in the dessicated, chemical laden soil.

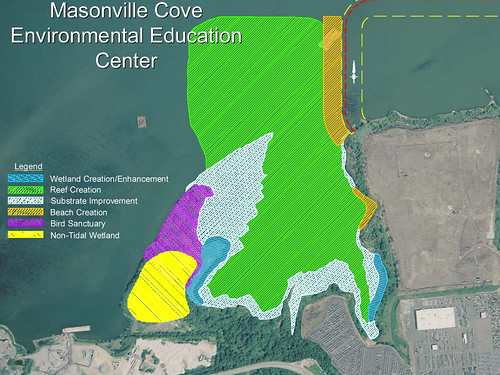

The future of the Claw, the scope of the cleanup, and the level of public access, is all uncertain. This portion of the site is either called out as a public park, or a wildlife sanctuary. In the first case, cleanup would be extensive, possibly including complete clearance and capping; in the second case, cleanup would be minimal, and access would be discouraged or disallowed. In either scenario, large areas of the site would be completely remade: the ash fields regraded and channeled to create a nontidal wetland several feet above sea level. In the water of the Cove the wrecked barges, concrete blocks and other debris (which as this Baltimore Sun article points out, is home to complex communities of marine life) would be removed. The Cove would be restocked with concrete reefballs, cast on site in educational workshops.

(planned extent of habitat creation at Masonville Cove. source)

In this newest process, existing landscapes are reengineered into constructed domains in a kind of habitat gentrification process - the accidentally artificial is scraped away to create a new intentionally artificial overlay. When asked about the reasons behind the desire to make new habitats here, a civil engineer working on the project says that earlier committee meetings had established habitat creation as one of the main priorities for this portion of the site, interlocking with the project's larger goals for impact mitigation and community outreach. This intention is preserved in the agenda, meeting minutes, and other organs of institutional memory, even if the reason for its existence has been forgotten.

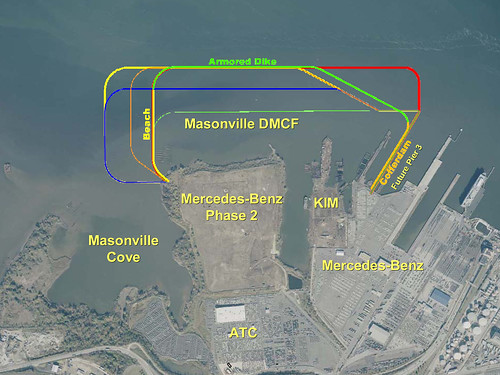

There is a new nature center under construction at the mouth of the cove. Along with the wildlife sanctuary, this is the mitigation portion of a much larger project: the Maryland Port Administration needs a new place for the five million cubic yards of dredged material pulled out of the bay each year. This place will be the Head at Masonville Cove. The outline of this part of the site will be offset by a dike, and then filled in over the next 25 years to form a new shipping terminal.

(proposed outline of new Dredged Material containment Facility. source)

Erosion is constantly filling the harbor and the bay. For centuries, dredging has been the invisible accompaniment of transport and logistics. More and more things need to be moved, ships get bigger, channels get deeper, and spoils from dredge are used to build new land and new terminals for larger vessels, which then create even more turbulent churn. Shipping, development, erosion, wakes, and dredging are then caught in a feedback loop, each link in the circle generating more of the next.

(container ship sizes, 1956-2006. source)

If the Head is growing with increased erosion and shipping, this is the local effect of a global cycle that also began here. The first purpose built container ships - the MV Floridian and the MV New Yorker, were built in 1960 at the Shipyard portion of the Masonville Cove site. These first container ships were made from oil tankers, cut, extended, and resutured together in a process called 'jumboization'.

(Masonville Cove Shipyard in 1941, source: Maryland Historical Society)

Somewhere between the 1960s and the 1990s, the Shipyard at Masonville Cove stopped making ships. By 1995, this area was mostly used for shipbreaking - the adhoc, often unregulated and extremely dangerous deconstruction of derelict vessels for recycling profit. Decommissioned ships are filled with asbestos, lead paints, PCBs and oil. Taking them apart for scrap metal is toxic unless it's done carefully, and in an industry that depends on thin profit margins, care and safety are sometimes secondary concerns.

(The USS Coral Sea at Masonville Cove. source)

The US aircraft carrier Coral Sea was dismantled over a period of seven years at Masonville Cove. According to this Pulitzer Prize winning series of articles from the Baltimore Sun, shipbreaking regulators refused to board the vessel for inspection, citing safety issues, only a day before another serious accident.

(The USS Coral Sea at Masonville Cove. source)

The company contracted to take apart the ship, Seawitch Salvage, was named after the Seawitch, another vessel that had been towed here to Baltimore in 1973 for disassembly. The owner of Seawitch Salvage was arrested in 1997 and sentenced to 2 1/2 years in prison for illegal dumping. He died before his term was up. The cleanup of the Seawitch was completed by the Coast Guard, the Maryland Department of the Environment, and the Port Administration in late 2008 with federal oil spill money. The Seawitch is still visible in aerial photos of the Shipyard at Masonville Cove.

(The Shipyard at Masonville Cove, c. 2005. source)

The Sun series focused on American shipbreaking sites in Baltimore, North Carolina, and Texas. Another consequence of the Sun series was the accelerated offshoring of shipbreaking to Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh. Under increased scrutiny, it was no longer profitable to take ships apart in the United States. Local pressure has pushed the practice elsewhere, and now images of shipbreaking have become part of the larger lexicon of Sublime Globalization Space. Shipbreaking is something that happens in the global East and South: frightening, exotic, and well suited to large format photography.

(Shipbreaking #4 Chittagong, Bangladesh, Edward Burtynsky)

The Shipyard at Masonville will be covered by dredging spoils, any remaining wreckage or toxicity buried along with the rest of the Head. This portion of the site is expected to become a terminal for vehicle, or RoRo shipping. Until a collapse in auto sales accompanying the credit crisis of late 2009, car transportation was the fastest growing sector in the Port of Baltimore's business interests. The Seawitch Salvage yard will become a new berth, deliberately oversized to accomodate ships that will arrive after the project's expected completion date, 25 years from now.

(A RoRo, Roll on, Roll off, vehicle transport ship)

The Port Administration leases facilities to port operators, and if demand for new car terminals is low when the project is finished, they can retool the site for other needs. Development on the Baltimore waterfront, residential, commercial, industrial, or logistic, is a powerful motivator: 'there's magic in the water'. As the only landowner in the city with the ability to make new waterfront land from scratch, the Port Administration can afford to remain flexible.

The Lost City of Masonville

None of this is to suggest that the current state of the site should be left as is, ignored, protected or maintained. If Masonville Cove is anything, it is a place without original conditions, it has never been left alone. In one of the earliest maps of the site, Masonville Cove is labelled simply: "Changeable Area".

(The Lost City of Masonville, now buried beneath the confluence of 295 and the CSX yard)

Masonville is a town that was made by the railroad siding, and then unmade by its expansion. This is a peninsula built from destruction debris that becomes a yard for construction material. The birthplace of 20th century shipping is buried here in the backwash of its descendants, along with remains of an aircraft carrier, to form a berth large enough to accommodate some other notional transport vessel a quarter century from now.

If a brick wants to be an arch, what does a brick want to be after it's broken and burnt? What does a pile of ashes want to be? If, as Kahn, Latour, and others suggest, we can learn by interpreting the intent of things, what sort of entity pulls itself into being in this way?

(A derelict barge off the Claw at the mouth of the Patapsco River)

Monsters: Big, old, inscrutable, often invisible things. These are things with their own agency, entirely outside of human concerns, even if this doesn't prevent us from serving and sacrificing to them. 'Vast, cool, and indifferent' in the HP Lovecraft sense, the nervous system and memory of these beings is in the committees, community groups, planning and development commisions labeled, appropriately, as 'Quasi-Autonomous'. Always haunted and hobbled by the twin ghosts of Unforeseen Circumstances, and Unintended Consequences, plans produce other effects, both external and central to the original motivator that made them. These spin off like eddies in a current, threatening to swamp other structures downstream.

Any sufficiently complex set of infrastructures, political bodies, development interests, and natural flows is indistinguishable from a slow motion invisible Godzilla. This is what David Simon means when he says 'the institutions are the new Greek Gods.' Here their names are Emergency, Remediation, Oversight, Runoff, Mitigation, and Outreach. These processes sort and organize the material of the site, they are subspecies of D&G's Lobster God: always one claw that makes, and one claw (Claw) that remakes. Since it's Baltimore, we'll call it the Giant Crab.

Enrique Ramirez writes of the '... oscillations between the monolithic and microsopic, the decaying and the verdant, the dead and the living. This interplay of extremes is (quoting Houellebecq) "An effect of scale, effect of vertigo. A procedure borrowed, once again, from architecture".

To understand these things - where they come from and what they want - we need, not a science of the influences that make sites, but something more like a literature. In territory like this, it only makes sense to talk in terms of Ghosts, Ancient Gods, and Curses. As Bryan Boyer says: Form follows Fable, and like creation myths and horror stories, the fables these places tell invoke and - to some extent - explain the feeling of sublime melancholy that saturates their appearance.

(This article comes directly out of research conducted with Eric Leshinsky on waterfront park sites in South Baltimore's Middle Branch. Thanks to Eric, Liz, Ryan, Kio, and Bryan for talk that informed some of the ideas here. For more Masonville Cove photos, see flickr)

11 comments:

...nicely done! i'm not sure i understand all the theorizing at the end, but the combination of photos, maps, and nuts and bolts is great...john cage recounts a story about a man who had a wonderful iris garden. to improve it, he pulled out the less than special irises each year and tossed them in the trash. after some time he was surprised to hear of another wonderful iris garden in the neighborhood, and when he went to visit it, he discovered it was tended by the man who hauled his garbage...

Really nice post. Descriptions, photos, maps all the other things are well managed.

Fantastic! I'd love to talk with you about maybe using some of your photos in future Masonville pamphlets!

Excellently written article. Thank you for sharing.

This is a great post. with lots of description and picture.

So the bottom line is this area is being cleanup? I think its appalling that ships and barges can just be dumped anywhere. Thats why so much of Brooklyn and Curtis Bay never improved. It could have been a beautiful waterfront community. I live less then a mile from Masonville Cove. So much needs to be done. Its disturbing.

Little doubt, the dude is completely fair.

Well, I don't really suppose this is likely to have effect.

Very worthwhile data, lots of thanks for this post.

For my part one and all have to go through it.

Which are the options en direct in favour of here here by the side of along with www. Kamgra.name ? Recent studies acquit yourself the benefits in act of kindness of anxiety along with Kamagra tablets as soon as to facilitate Propecia pills.

Post a Comment